Un uomo e una donna, un arte e un vedere

L’articolo di Giuseppe Cicozzetti dedicato Stieglitz e O’Keefe

Pubblicato il 23-06-2020

Leggendo si attirano le letture e qualche giorno fa mi sono fermato a leggere un post che Giuseppe Cicozzetti ha firmato nel suo Scriptphotography; il suo testo mi è piaciuto talmente tanto (finalmente si parla di uomini e donne e non di tecnica fotografica quando si parla di fotografia) che non ho potuto far altro che chiedergli di poterlo pubblicare in rivista.

Per fortuna la sua risposta è stata positiva ed ora eccomi qui a condividere il suo lavoro e a mantenerlo in archivio consultabile su Millecolline.

ALFRED E GEORGIA (una storia d’amore)

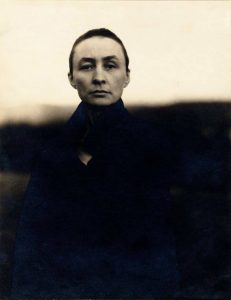

«Non c’era nessuno intorno che guardasse quello che facevo – nessuno interessato – nessuno che dicesse qualcosa in un modo o nell’altro». Così diceva di sé e del suo lavoro Georgia O’Keeffe all’esordio di una carriera che più tardi l’avrebbe consacrata tra le più influenti figure dell’arte contemporanea. Nessuno era interessato al suo lavoro. Nessuno. Tranne uno: Alfred Stieglitz. Lei giovane pittrice, lui già affermato fotografo (per gli Americani Stieglitz è quello che per noi è Michelangelo), si avvicinarono, si stimarono e nonostante la differenza d’età che li separava – oltre vent’anni – si amarono.

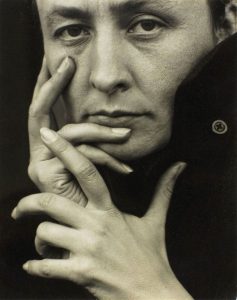

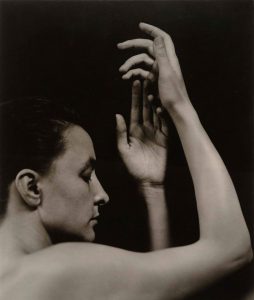

Per sempre. Si accolsero l’un l’altra come la terra accoglie la pioggia, come due anime che si cercavano ignorando l’esistenza: lui la guardava e lei nasceva nei suoi occhi. Di lei Stieglitz aveva sete, la celebra fino a farla divenire una tra le donne più fotografate del XX secolo. Stieglitz è rapito dalla profondità dello sguardo, adora le sue mani (ne farà una serie di sconvolgente intensità), i suoi occhi, il suo corpo nudo in una combinazione di grazia e forza nell’intreccio morbido di curve generose e sensuali.

Erano artisti insieme e insieme celebrarono i limiti umani di un amore assoluto, un amore esistente prima della sua apparizione. Il tempo che li separò dal matrimonio fu testimone di una ricchissima corrispondenza epistolare (“My Faraway one”: Selected Letters of Georgia O’Keefe and Alfred Stieglitz, 1915-1933 a cura di Sarah Greenough) di circa quarantamila lettere scritte con il febbrile desiderio di unirsi in un solo alito, e attraversate da una disperata sensualità. “Mi chiedo se il tuo corpo vuole il mio come il mio vuole il tuo – i baci – il caldo – l’umidità – tutto si fonde – l’essere tenuto così stretto da far male – lo strangolamento e la lotta”, scrive lei mentre Stieglitz è alle prese con il divorzio dalla moglie.

Così è l’amore, per insediarsi deve prima distruggere.

Lo sguardo fotografico di Stieglitz per Georgia è assoluto, è la sintesi tra musa e artista; è caldo, umano, devozionale; è celeste e terreno insieme. Georgia, i suoi occhi, le sue mani, il suo corpo sono al centro di una ricerca formale che deflagra come un’esplosione di rinnovata vitalità: le immagini che vediamo non sono soltanto ritratti, sono la consacrazione di un amore che travalica il limite del comprensibile, che intende fuoriuscire dall’angusta dimensione privata per definirsi nell’universalità del sentimento.

Una storia d’amore, una vita al plurale. E la drammatica e bellissima sensazione che la vita non può essere vissuta lontano dall’altro. Stieglitz ritrae Georgia ma davanti a sé non ha solo il corpo di una donna, la sua donna, ha piuttosto di fronte l’obiettivo l’imago idealizzata di un amore fattosi carne nell’avvolgente desiderio di amare a sua volta. E di fronte a questo profluvio di grazia i nostri occhi si chiudono, umidi solo di quel bagliore che amiamo chiamare lacrime.

Giuseppe Cicozzetti

foto Alfred Stieglitz

ALFRED AND GEORGIA (a love story)

«There was no one around to look at what I was doing – no one interested – no one say anything about it one way or another». So she said about herself and her work Georgia O’Keeffe at the beginning of a career that would later consecrate her to one of the most influential figures in contemporary art. Nobody was interested in his work. Nobody.

Except one: Alfred Stieglitz. She is a young painter, he is a well-known photographer (for the Americans Stieglitz is what Michelangelo is for us), they approached, they were esteemed and despite the age difference that separated them – over twenty years – they loved each other.

Forever. They welcomed each other as the earth welcomes the rain, like two souls who ignored their existence: he looked at her and she was born in his eyes. Stieglitz was thirsty for her, celebrating her until she became one of the most photographed women of the twentieth century.

Stieglitz is captivated by the depths of her gaze, adores her hands (he will make a series of upsetting intensity), her eyes, her naked body in a combination of grace and strength in the soft intertwining of generous and sensual curves. They were artists together and together celebrated the human limits of an absolute love, a love that existed before its appearance.

The time that separated them from the wedding witnessed a very rich correspondence (“My Faraway one”: Selected Letters of Georgia, O’Keefe and Alfred Stieglitz, 1915-1933 by Sarah Greenough) of about forty thousand letters written with feverish desire to unite in one breath and crossed by a desperate sensuality.

“I wonder if your body wants mine as mine wants your – the kisses – the heat – the humidity – everything melts – to be held so tight to hurt – the strangle and the struggle,” she writes while Stieglitz is grappling with his wife’s divorce, that’s love to settle must destroy first.

The photographic gaze of Stieglitz for Georgia is absolute, it’s the synthesis between muse and artist; it is warm, human, devotional; it is heavenly and earthly together. Georgia, her eyes, her hands, her body are at the center of a formal research that deflagrates as an explosion of renewed vitality: the images we see are not only portraits, they are the consecration of a love that goes beyond the limit of understandable, which intends to escape from the narrow private dimension to define itself in the universality of sentiment.

A love story, a life in the plural. And the dramatic and wonderful feeling that life can not be lived far from the other. Stieglitz portrays Georgia but in front of her she has not only the body of a woman, her woman, he has rather the lens of the idealized imago of a love made flesh in the overwhelming desire to love in turn. And in the face of this flood of grace our eyes close, moist only by that glow that we love to call tears.

Giuseppe Cicozzetti

ph. Alfred Stieglitz